DEFINING THE ALEXANDER TECHNIQUE Tim

Soar © 1999

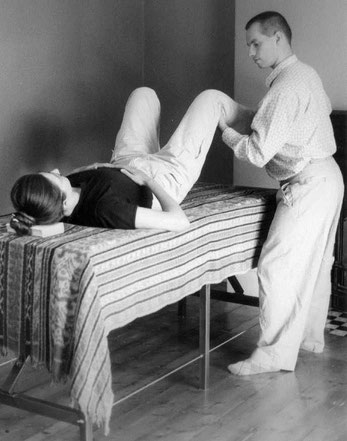

3. Non-Doing and Working on the Table

The Alexander Technique seeks to refine activities such as postural co-ordination, balance, breathing and fundamental movement patterns such as walking.

The basic organisation of these activities is not subject to our direct deliberate control (in the sense that finger movement in playing the piano is under direct control, for example), but neither is it completely automatic and beyond any conscious intervention (in the way that contraction and dilation of your arteries is completely automatic, for example).

In a well coordinated person the basic patterns of movement are organised largely automatically, whilst remaining available to conscious modification; for example, breathing may be modified, to control the out-breath for speaking, or walking may be modified to avoid stepping in a puddle. Immediately following any such modification we should return easily to a neutral “non-modified” or “non-interfered-with” state of balance.

This state of neutral balance can be observed (as a source of inspiration!) in healthy young children. However, as we grow up it often becomes more and more elusive.

The Alexander Technique, therefore is concerned with the rediscovery of this neutral “non-doing” state in which balance, postural coordination, breathing and other basic bodily functions are not interfered with, but are left alone to “organise themselves”.

This skill of non-doing or “leaving yourself alone” – of stopping distorting part of yourself in order that it can correct itself – is the keystone of the Alexander Technique; it forms a large part of the concept Alexander named inhibition1 upon which, he said, his Technique is based.2

In learning and practising the Alexander Technique, it is important to avoid “trying to get it right” but rather to cultivate the attitude:

If I can stop doing the wrong thing, then the right thing will do itself.

Lying semi-supine is the most effective way to establish an awareness of non-doing, but this awareness can and should be applied in progressively more demanding situations, so that eventually you can perform even skilled or stressful tasks without compromising the efficiency of your basic functioning – breathing, postural activity, breadth of awareness, and so on.

Thus, improvement comes about not by learning to move properly, but rather by learning how not to interfere with natural movement.

In a lesson, when your teacher works on you whilst you are lying semi-supine, either on the floor, or more usually on a table, you have the opportunity to practise non-doing to a degree which you could not reach by yourself and which would not normally be possible when you are sitting or standing

Free from the possibility of falling, you can allow yourself to be supported by the table and by your teacher’s hands.

If your teacher moves one of your limbs, or your head, or part of your torso, you should aim to allow the movement to be free and light – not stiffening in such a way as to prevent the movement.

Once you have allowed your teacher, for example, to lift one of your legs, there are two likely ways in which you may interfere with its freedom of movement:

- “Helping” by anticipating any further movement, or holding up the weight of the leg yourself.

- Being a “sack of potatoes”, a dull, lifeless dead weight.

If you can avoid both of these mistakes, you will begin to become truly poised and free moving – integrated and strong, yet free from tension.

1 Inhibition : Conscious and ongoing prevention of habitual interference with optimum poise: one of the principal skills of the Technique.

2 The Universal Constant in Living, FM Alexander, 1941, Chapter 5, “The Constant Influence of Manner of Use in Relation to Change”.